TRA LA MIROR

La casa mirorida ·

La jardin de flores vivente ·

Insetos mirorida ·

Rococin e Rococon ·

Lana e acua ·

Ovaluna ·

Leon e Unicorno ·

“Me mesma ia inventa lo” ·

Un vespa perucida ·

Rea Alisia ·

Luta ·

Muta ·

Ci ia fa la sonia?

Chapter V. WOOL AND WATER.

El catura la xal a cuando el parla, e xerca sirca se la posesor: pos un plu momento, la Rea Blanca veni savaje corente tra la bosce, con ambos brasos larga estendeda, como si el ta vola, e Alisia vade multe sivil con la xal per encontra el.

She caught the shawl as she spoke, and looked about for the owner: in another moment the White Queen came running wildly through the wood, with both arms stretched out wide, as if she were flying, and Alice very civilly went to meet her with the shawl.

“Me es multe felis ce me ia pote acaso bloci lo,” Alisia dise, aidante el a apone denova sua xal.

“I’m very glad I happened to be in the way,” Alice said, as she helped her to put on her shawl again.

La Rea Blanca fa no plu ca regarda el en un manera de spesie asustada e nonprotejeda, e repete en un xuxa constante a se alga cosa cual sona como “pan burida, pan burida”, e Alisia senti ce si an cualce conversa va aveni, el mesma va debe dirije lo. Donce el comensa alga timida: “Esce me parla… ja con… la Rea Blanca?”

The White Queen only looked at her in a helpless frightened sort of way, and kept repeating something in a whisper to herself that sounded like “bread-and-butter, bread-and-butter,” and Alice felt that if there was to be any conversation at all, she must manage it herself. So she began rather timidly: “Am I addressing the White Queen?”

“Si, bon – si on pote nomi un xal un ‘jacon’,” la Rea dise. “Lo no conforma a mea idea de un jacon, tota no.”

“Well, yes, if you call that a-dressing,” the Queen said. “It isn’t my notion of the thing, at all.”

Alisia pensa ce lo ta conveni nunca si los fa un disputa a la comensa mesma de sua conversa, donce el surie e dise, “Si tu va indica mera la modo coreta de comensa, Altia, me va pote ja continua en la mesma modo.”

Alice thought it would never do to have an argument at the very beginning of their conversation, so she smiled and said, “If your Majesty will only tell me the right way to begin, I’ll do it as well as I can.”

“Ma me tota no desira un jacon!” la Rea povre jemi. “Me es ja vestinte me tra la du oras pasada.”

“But I don’t want it done at all!” groaned the poor Queen. “I’ve been a-dressing myself for the last two hours.”

Lo ta es multe plu bon, en la opina de Alisia, si el ta demanda ce algun otra ta vesti el, car el es tan xocante desordinada. “An no un cosa es reta,” Alisia pensa a se, “e el es covreda con spinos!—esce tu vole ce me reti tua xal per tu?” el ajunta a vose.

It would have been all the better, as it seemed to Alice, if she had got some one else to dress her, she was so dreadfully untidy. “Every single thing’s crooked,” Alice thought to herself, “and she’s all over pins!–may I put your shawl straight for you?” she added aloud.

“Me no sabe perce lo malcondui!” la Rea dise, en un vose triste. “Lo no es en bon umor, me pensa. Me ia spini lo asi, e me ia spini lo ala, ma me es tota noncapas de contenti lo!”

“I don’t know what’s the matter with it!” the Queen said, in a melancholy voice. “It’s out of temper, I think. I’ve pinned it here, and I’ve pinned it there, but there’s no pleasing it!”

“Lo no pote senta reta, tu sabe, si tu spini tota partes de lo a un lado,” Alisia dise, jentil coretinte lo per el; “e, ai! tua capeles es en un state tan mal!”

“It can’t go straight, you know, if you pin it all on one side,” Alice said, as she gently put it right for her; “and, dear me, what a state your hair is in!”

“La brosa ia deveni maraniada en los!” la Rea dise con suspira. “E me ia perde ier la peten.”

“The brush has got entangled in it!” the Queen said with a sigh. “And I lost the comb yesterday.”

Alisia libri la brosa con atende, e fa la plu bon cual el pote per ordina la capeles. “Vide, tu aspeta alga plu bon aora!” el dise, pos altera la plu de la spinos. “Ma vera, tu debe emplea un aidor de dama!”

Alice carefully released the brush, and did her best to get the hair into order. “Come, you look rather better now!” she said, after altering most of the pins. “But really you should have a lady’s maid!”

“Me va emplea tu con plaser!” la Rea dise. “Du peniges per semana, con jalea a la dia du de cada duple.”

“I’m sure I’ll take you with pleasure!” the Queen said. “Twopence a week, and jam every other day.”

Alisia no pote evita rie en cuando el dise, “Me no vole ce tu emplea me—e me no gusta jalea.”

Alice couldn’t help laughing, as she said, “I don’t want you to hire me–and I don’t care for jam.”

“Lo es un jalea multe bon,” la Rea dise.

“It’s very good jam,” said the Queen.

“Ma me no desira lo oji, an tal.”

“Well, I don’t want any to-day, at any rate.”

“Tu no ta pote ave lo an si tu ta desira lo,” la Rea dise. “La regula es: jalea doman e jalea ier—ma nunca jalea oji.”

“You couldn’t have it if you did want it,” the Queen said. “The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday–but never jam to-day.”

“‘Jalea oji’ debe aveni a veses,” Alisia protesta.

“It must come sometimes to ‘jam to-day,’” Alice objected.

“No, nonposible,” la Rea dise. “On ave jalea a la dia du de cada duple: ma oji es sola un dia, tu sabe.”

“No, it can’t,” said the Queen. “It’s jam every other day: to-day isn’t any other day, you know.”

“Me no comprende tu,” Alisia dise. “Lo es estrema confusante!”

“I don’t understand you,” said Alice. “It’s dreadfully confusing!”

“Acel es la efeto de vive en reversa,” la Rea dise compatiosa: “on deveni sempre alga mareada per comensa—”

“That’s the effect of living backwards,” the Queen said kindly: “it always makes one a little giddy at first–”

“Vive en reversa!” Alisia repete con stona grande. “Me ia oia nunca un tal idea!”

“Living backwards!” Alice repeated in great astonishment. “I never heard of such a thing!”

“—ma on reseta esta vantaje grande de lo, ce sua memoria funsiona en ambos dirijes.”

“–but there’s one great advantage in it, that one’s memory works both ways.”

Me es serta ce la mea funsiona en sola un dirije,” Alisia comenta. “Me no pote recorda un cosa ante sua aveni.”

“I’m sure mine only works one way,” Alice remarked. “I can’t remember things before they happen.”

“Un memoria es alga povre si lo recorda sola la pasada,” la Rea comenta.

“It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards,” the Queen remarked.

“Cual cosas tu recorda la plu bon?” Alisia osa demanda.

“What sort of things do you remember best?” Alice ventured to ask.

“O, avenis en la semana pos la veninte,” la Rea responde en un tono casual. “Per esemplo,” el continua, ponente un peso grande de bandaje sur sua dito en cuando el parla, “considera la Mesajor de la Re. El es aora en prison, per es punida: e la prosede no va comensa an asta la mercurdi veninte: e natural, la crimin va aveni final de tota.”

“Oh, things that happened the week after next,” the Queen replied in a careless tone. “For instance, now,” she went on, sticking a large piece of plaster on her finger as she spoke, “there’s the King’s Messenger. He’s in prison now, being punished: and the trial doesn’t even begin till next Wednesday: and of course the crime comes last of all.”

“Ma cisa el va fa nunca la crimin?” Alisia dise.

“Suppose he never commits the crime?” said Alice.

“Acel ta es multe plu bon, no?” la Rea dise, liante la banda sirca sua dito con un peso peti de sinta.

“That would be all the better, wouldn’t it?” the Queen said, as she bound the plaster round her finger with a bit of ribbon.

Alisia senti ce el no pote nega esta. “Natural, lo ta es multe plu bon,” el dise: “ma lo no ta es multe plu bon ce on ia puni ja el.”

Alice felt there was no denying that. “Of course it would be all the better,” she said: “but it wouldn’t be all the better his being punished.”

“Tu era sur acel punto, an tal,” la Rea dise: “esce on ia puni nunca tu?”

“You’re wrong there, at any rate,” said the Queen: “were you ever punished?”

“Sola per atas sur cual me ia es culpable,” Alisia dise.

“Only for faults,” said Alice.

“E tu ia deveni multe plu bon pos la puni, me sabe!” la Rea dise vinsente.

“And you were all the better for it, I know!” the Queen said triumphantly.

“Si, ma alora me ia fa la atas per cual on ia puni me,” Alisia dise: “acel es completa diferente.”

“Yes, but then I had done the things I was punished for,” said Alice: “that makes all the difference.”

“Ma si tu no ia ta fa los,” la Rea dise, “acel ia ta es an plu bon; plu bon, e plu bon, e plu bon!” Sua vose deveni plu alta a cada “bon”, e fini par sona vera simil a un pia.

“But if you hadn’t done them,” the Queen said, “that would have been better still; better, and better, and better!” Her voice went higher with each “better,” till it got quite to a squeak at last.

Alisia es a comensa de dise “Tu era en alga modo—”, cuando la Rea comensa xilia tan forte ce el debe abandona la fini de la frase. “O! o! o!” la Rea cria, secutente sua mano de asi a ala como si el vole secute lo a via. “Mea dito sangui! O! o! o! o!”

Alice was just beginning to say “There’s a mistake somewhere–,” when the Queen began screaming so loud that she had to leave the sentence unfinished. “Oh, oh, oh!” shouted the Queen, shaking her hand about as if she wanted to shake it off. “My finger’s bleeding! Oh, oh, oh, oh!”

Sua xilias es tan esata simil a la sibila de un locomotiva de vapor ce Alisia debe covre sua oreas con ambos manos.

Her screams were so exactly like the whistle of a steam-engine, that Alice had to hold both her hands over her ears.

“Cua es la problem?” el dise, a la momento prima cuando el ta pote es oiada. “Esce tu ia pica tua dito?”

“What is the matter?” she said, as soon as there was a chance of making herself heard. “Have you pricked your finger?”

“Me ancora no ia pica lo,” la Rea dise, “ma me va pica lo pronto—o! o! o!”

“I haven’t pricked it yet,” the Queen said, “but I soon shall–oh, oh, oh!”

“Cuando la pica va aveni en tua previde?” Alisia demanda, sentinte un disposa forte a rie.

“When do you expect to do it?” Alice asked, feeling very much inclined to laugh.

“Direta cuando me refisa mea xal,” la Rea povre dise jeminte: “la brox va deveni desfisada. O! o!” A cuando el dise la parolas, la brox abri subita, e la Rea saisi savaje lo, en atenta refisa lo.

“When I fasten my shawl again,” the poor Queen groaned out: “the brooch will come undone directly. Oh, oh!” As she said the words the brooch flew open, and the Queen clutched wildly at it, and tried to clasp it again.

“Atende!” Alisia esclama. “Tu teni tota nonreta lo!” E el atenta saisi la brox; ma lo es tro tarda: la spino lisca ja, e la Rea pica ja sua dito.

“Take care!” cried Alice. “You’re holding it all crooked!” And she caught at the brooch; but it was too late: the pin had slipped, and the Queen had pricked her finger.

“Acel esplica la sangui, tu vide,” el dise a Alisia con un surie. “Aora tu comprende como avenis funsiona asi.”

“That accounts for the bleeding, you see,” she said to Alice with a smile. “Now you understand the way things happen here.”

“Ma perce tu no xilia aora?” Alisia demanda, con sua manos preparada per covre sua oreas denova.

“But why don’t you scream now?” Alice asked, holding her hands ready to put over her ears again.

“Car me ia fa ja tota la xilias,” la Rea dise. “Como me ta es beneficada par fa denova los?”

“Why, I’ve done all the screaming already,” said the Queen. “What would be the good of having it all over again?”

Aora, la loca deveni ja luminada. “Serta, la corvo ia vola a via, me pensa,” Alisia dise: “me es tan felis ce el ia parti. Me ia suposa ce la note prosimi.”

By this time it was getting light. “The crow must have flown away, I think,” said Alice: “I’m so glad it’s gone. I thought it was the night coming on.”

“Me desira ce me ta pote susede es felis!” la Rea dise. “Ma me recorda nunca la metodo. Tu es clar multe felis, abitante en esta bosce, e esente felis sempre cuando tu vole!”

“I wish I could manage to be glad!” the Queen said. “Only I never can remember the rule. You must be very happy, living in this wood, and being glad whenever you like!”

“An tal, me es tan multe solitar asi!” Alisia dise en un vose triste; e, a la pensa de sua solitaria, du larmas grande desende rolante sua jenas.

“Only it is so very lonely here!” Alice said in a melancholy voice; and at the thought of her loneliness two large tears came rolling down her cheeks.

“O! no continua en acel modo!” la Rea povre esclama, torsente sua manos en despera. “Considera ce tu es un xica tan grande. Considera ce tu ia veni oji sur un via tan longa. Considera cual es la ora. Considera cualce cosa, ma no plora!”

“Oh, don’t go on like that!” cried the poor Queen, wringing her hands in despair. “Consider what a great girl you are. Consider what a long way you’ve come to-day. Consider what o’clock it is. Consider anything, only don’t cry!”

Alisia no pote evita rie a esta, an en media de sua larmas. “Esce tu pote evita plora par consideras?” el demanda.

Alice could not help laughing at this, even in the midst of her tears. “Can you keep from crying by considering things?” she asked.

“Par acel metodo on susede,” la Rea dise multe desidosa: “nun es capas de fa du cosas a la mesma tempo, tu sabe. Ta ce nos considera tua eda per comensa—cuanto anios tu ave?”

“That’s the way it’s done,” the Queen said with great decision: “nobody can do two things at once, you know. Let’s consider your age to begin with–how old are you?”

“Me ave sete e un dui anios, esata.”

“I’m seven and a half exactly.”

“Tu no nesesa dise ‘es data,’” la Rea comenta. “Me pote crede lo sin acel. Aora me va dona a tu un cosa per crede. Me ave ja sento-un anios, sinco menses, e un dia.”

“You needn’t say ‘exactually,’” the Queen remarked: “I can believe it without that. Now I’ll give you something to believe. I’m just one hundred and one, five months and a day.”

“Me no pote crede acel!” Alisia dise.

“I can’t believe that!” said Alice.

“No?” la Rea dise en un tono compatiante. “Atenta denova: fa un enspira longa, e clui tua oios.”

“Can’t you?” the Queen said in a pitying tone. “Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes.”

Alisia rie. “La atenta no va susede,” el dise: “on no pote crede cosas nonposible.”

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“Me suposa ce tu no ia pratica multe lo,” la Rea dise. “Cuando me ia ave tua eda, me ia fa sempre lo per un dui de ora a cada dia. Vera, a veses, me ia crede no min ca ses cosas nonposible ante la come de matina. La xal vola denova!”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast. There goes the shawl again!”

La brox ia desfisa se en cuando el ia parla, e, par un soflon subita de venta, la xal de la Rea vola a traversa de un rieta peti. La Rea estende denova sua brasos, e core per xasa lo, e, a esta ves, el mesma susede catura lo. “Me ave lo!” el esclama en un tono de vinse. “Aora tu va vide ce me spini lo a me denova, me mesma, sin aida!”

The brooch had come undone as she spoke, and a sudden gust of wind blew the Queen’s shawl across a little brook. The Queen spread out her arms again, and went flying after it, and this time she succeeded in catching it for herself. “I’ve got it!” she cried in a triumphant tone. “Now you shall see me pin it on again, all by myself!”

“Donce me espera ce tua dito senti plu bon aora?” Alisia dise multe jentil, en cuando el traversa la rieta peti pos la Rea.

“Then I hope your finger is better now?” Alice said very politely, as she crossed the little brook after the Queen.

* * * * * * *

* * * * * *

* * * * * * *

“O! multe plu bon!” la Rea esclama, e sua vose alti a un pia en cuando el continua. “Multe plu bo-on! Bo-on! Bo-o-a-an! Ba-a-a-a-a!” La parola final fini con un maa longa, tan simil a un ovea ce Alisia salteta vera.

“Oh, much better!” cried the Queen, her voice rising to a squeak as she went on. “Much be-etter! Be-etter! Be-e-e-etter! Be-e-ehh!” The last word ended in a long bleat, so like a sheep that Alice quite started.

El regarda la Rea, ci pare subita envolveda en lana. Alisia frota sua oios, e regarda denova. El tota no pote comprende cua ia aveni. Esce el es en un boteca? E vera, esce acel es—esce lo es vera un ovea ci senta a la otra lado de la table de vende? An con tota sua frotas, el no pote comprende plu la situa: el es en un peti boteca oscur, apoiante sua codos sur la table de vende, e a fas de el un Ovea vea senta tricotante sur un seja de brasos, e sesante de ves a ves per regarda el tra un oculo grande.

She looked at the Queen, who seemed to have suddenly wrapped herself up in wool. Alice rubbed her eyes, and looked again. She couldn’t make out what had happened at all. Was she in a shop? And was that really–was it really a sheep that was sitting on the other side of the counter? Rub as she could, she could make nothing more of it: she was in a little dark shop, leaning with her elbows on the counter, and opposite to her was an old Sheep, sitting in an arm-chair knitting, and every now and then leaving off to look at her through a great pair of spectacles.

“Cua tu desira compra?” la Ovea dise final, levante sua regarda de sua tricota per un momento.

“What is it you want to buy?” the Sheep said at last, looking up for a moment from her knitting.

“Me ancora no sabe intera,” Alisia dise, multe jentil. “Me ta vole prima regarda tota a sirca de me, si me pote.”

“I don’t quite know yet,” Alice said, very gently. “I should like to look all round me first, if I might.”

“Tu pote regarda ante tu, e a ambos lados, si tu vole,” la Ovea dise: “ma tu no pote regarda tota a sirca de tu—estra si tu ave oios a retro de tua testa.”

“You may look in front of you, and on both sides, if you like,” said the Sheep: “but you can’t look '‘all’ round you–unless you’ve got eyes at the back of your head.”

Ma, par acaso, Alisia no ave estas: donce el contenti se con turna en sirculo, regardante cada scafal cuando el ateni lo.

But these, as it happened, Alice had not got: so she contented herself with turning round, looking at the shelves as she came to them.

La boteca pare plen de tota spesies de cosas nonusual—ma la cualia la plu strana de tota es ce, sempre cuando el regarda intensa cualce scafal per persepi esata cua lo porta, acel scafal mesma es sempre intera vacua, an si la otras sirca lo es tan plenida ce los no ta pote conteni plu.

The shop seemed to be full of all manner of curious things–but the oddest part of it all was, that whenever she looked hard at any shelf, to make out exactly what it had on it, that particular shelf was always quite empty: though the others round it were crowded as full as they could hold.

“La cosas asi es tan fluosa!” el dise final en un tono lamentin, pos pasa cuasi un minuto en xasa futil un cosa grande e colorosa cual aspeta a veses como un pupa e a veses como un caxa de utiles, e cual es sempre sur la scafal direta supra lo cual el regarda. “E esta es la plu provocante de tota—ma me ave un idea—” el ajunta, cuando un pensa subita ariva en sua mente, “me va segue lo a supra asta la scafal la plu alta de tota. Lo va es confondeda e noncapas de vade tra la sofito, me previde!”

“Things flow about so here!” she said at last in a plaintive tone, after she had spent a minute or so in vainly pursuing a large bright thing, that looked sometimes like a doll and sometimes like a work-box, and was always in the shelf next above the one she was looking at. “And this one is the most provoking of all–but I’ll tell you what–” she added, as a sudden thought struck her, “I’ll follow it up to the very top shelf of all. It’ll puzzle it to go through the ceiling, I expect!”

Ma an esta scema fali: la “cosa” vade tan cuieta como posible tra la sofito, como si lo es intera abituada a esta.

But even this plan failed: the “thing” went through the ceiling as quietly as possible, as if it were quite used to it.

“Esce tu es un enfante o un jireta?” la Ovea dise, prendente un otra duple de agos de tricota. “Me va es pronto mareada, si tu continua turna tal.” El labora aora con des-cuatro duples a la mesma tempo, e Alisia no pote evita regarda el con stona grande.

“Are you a child or a teetotum?” the Sheep said, as she took up another pair of needles. “You’ll make me giddy soon, if you go on turning round like that.” She was now working with fourteen pairs at once, and Alice couldn’t help looking at her in great astonishment.

“Como el pote tricota con tan multe?” la enfante confondeda pensa a se. “El sembla sempre plu un porcospina a cada minuto!”

“How can she knit with so many?” the puzzled child thought to herself. “She gets more and more like a porcupine every minute!”

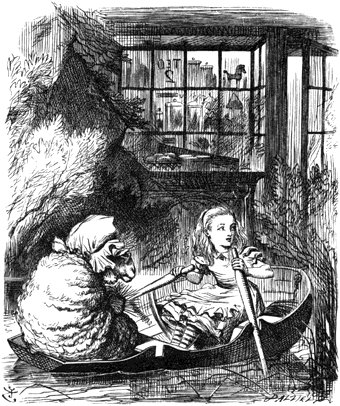

“Tu pote remi?” la Ovea demanda, donante a el un duple de agos de tricota en cuando el parla.

“Can you row?” the Sheep asked, handing her a pair of knitting-needles as she spoke.

“Si, alga—ma no sur tera—e no con agos—” Alisia comensa dise, cuando subita la agos cambia se a remos en sua manos, e el trova ce los senta en un barco peti, liscante a longo entre rivas: donce el pote fa no otra cosa ca un atenta tan bon como posible.

“Yes, a little–but not on land–and not with needles–” Alice was beginning to say, when suddenly the needles turned into oars in her hands, and she found they were in a little boat, gliding along between banks: so there was nothing for it but to do her best.

“Pluma!” la Ovea esclama en jergo de remores, prendente un otra duple de agos.

“Feather!” cried the Sheep, as she took up another pair of needles.

Esta no sona como un comenta cual nesesa un responde, donce Alisia dise no cosa, ma tira plu la remos. La acua ave alga cualia multe strana, el pensa, car de ves a ves la remos deveni fisada en lo, e pote apena es estraeda denova.

This didn’t sound like a remark that needed any answer, so Alice said nothing, but pulled away. There was something very queer about the water, she thought, as every now and then the oars got fast in it, and would hardly come out again.

“Pluma! Pluma!” la Ovea esclama denova, prendente plu agos. “O tu va catura pronto un crabe.”

“Feather! Feather!” the Sheep cried again, taking more needles. “You’ll be catching a crab directly.”

“Un peti crabe cara!” Alisia pensa. “Me ta gusta acel.”

“A dear little crab!” thought Alice. “I should like that.”

“Esce tu no ia oia mea comanda de “Pluma?” la Ovea esclama coler, prendente vera un monton de agos.

“Didn’t you hear me say “Feather”?” the Sheep cried angrily, taking up quite a bunch of needles.

“Ma serta,” Alisia dise: “tu ia dise lo a multe veses–e multe forte. Per favore, do es la crabes?”

“Indeed I did,” said Alice: “you’ve said it very often–and very loud. Please, where are the crabs?”

“En la acua, natural!” la Ovea dise, ponente alga de la agos en sua capeles, car sua manos es plen. “Pluma, me dise!”

“In the water, of course!” said the Sheep, sticking some of the needles into her hair, as her hands were full. “Feather, I say!”

“Perce tu dise ‘pluma’ tan multe?” Alisia demanda final, alga frustrada. “Me no es un avia!”

“Why do you say ‘feather’ so often?” Alice asked at last, rather vexed. “I’m not a bird!”

“Ma si,” la Ovea dise: “tu es un ganso peti.”

“You are,” said the Sheep: “you’re a little goose.”

Esta ofende alga Alisia, donce on fa no plu conversa tra un o du minutos, tra cuando la barco lisca calma a ante, a veses entre fondos de malerbas (cual fisa la remos en la acua an plu ca a ante), e a veses su arbores, ma sempre con la mesma rivas alta cual grima supra sua testas.

This offended Alice a little, so there was no more conversation for a minute or two, while the boat glided gently on, sometimes among beds of weeds (which made the oars stick fast in the water, worse then ever), and sometimes under trees, but always with the same tall river-banks frowning over their heads.

“O! per favore! Me vide ala juncos parfumida!” Alisia esclama en un vola subita de deleta. “Vera, los es ala—e tan bela!”

“Oh, please! There are some scented rushes!” Alice cried in a sudden transport of delight. “There really are–and such beauties!”

“Tu no nesesa dise ‘per favore’ a me sur los,” la Ovea dise, sin leva sua regarda de sua tricota: “me no ia pone los ala, e me no va prende los a via.”

“You needn’t say ‘please’ to me about ’em,” the Sheep said, without looking up from her knitting: “I didn’t put ’em there, and I’m not going to take ’em away.”

“No, ma me ia vole dise—per favore, esce nos ta pote pausa e colie alga?” Alisia prea. “Si tu no oposa para la barco per un minuto.”

“No, but I meant–please, may we wait and pick some?” Alice pleaded. “If you don’t mind stopping the boat for a minute.”

“Como me ta para lo?” la Ovea dise. “Si tu sesa remi, lo va para se mesma.”

“How am I to stop it?” said the Sheep. “If you leave off rowing, it’ll stop of itself.”

Donce el lasa ce la barco vaga longo la rieta como lo vole, asta cuando lo lisca calma a entre la juncos pendulinte. E alora la mangas peti es atendosa rolada, e la brasos peti es tufada en la acua asta sua codos per saisi la juncos a un loca bon profonda ante rompe los a via—e, tra un tempo, Alisia oblida intera la Ovea e la tricota, estendente se en curva ultra la lado de la barco, lasante ce mera la finis de sua capeles maraniada toca la acua—en cuando, con oios briliante e zelosa, el prende sempre plu grupos de la cara juncos parfumida.

So the boat was left to drift down the stream as it would, till it glided gently in among the waving rushes. And then the little sleeves were carefully rolled up, and the little arms were plunged in elbow-deep to get the rushes a good long way down before breaking them off–and for a while Alice forgot all about the Sheep and the knitting, as she bent over the side of the boat, with just the ends of her tangled hair dipping into the water–while with bright eager eyes she caught at one bunch after another of the darling scented rushes.

“Me espera sola ce la barco no va inversa se!” el dise a se. “O! un junco tan deletosa! Ma lo ia es pico ultra mea estende.” E serta, lo pare vera alga provocante (“cuasi como si lo intende aveni,” el pensa) ce, an si el susede prende un abunda de juncos bela cuando la barco pasa liscante, el vide sempre un junco plu deletosa cual el no pote ateni.

“I only hope the boat won’t tipple over!” she said to herself. “Oh, what a lovely one! Only I couldn’t quite reach it.” And it certainly did seem a little provoking (“almost as if it happened on purpose,” she thought) that, though she managed to pick plenty of beautiful rushes as the boat glided by, there was always a more lovely one that she couldn’t reach.

“La plu atraosas es sempre plu distante!” el dise final, con suspira a la ostina de la juncos cual crese tan distante, cuando, con jenas rojida e capeles e manos gotante, el trepa denova a sua loca, e comensa ordina sua tesoros nova trovada.

“The prettiest are always further!” she said at last, with a sigh at the obstinacy of the rushes in growing so far off, as, with flushed cheeks and dripping hair and hands, she scrambled back into her place, and began to arrange her new-found treasures.

A esta momento, lo importa tan poca a el ce la juncos comensa ja pali, e perde tota sua parfum e belia, an direta cuando el ia prende los. An juncos parfumida cual es real dura tra sola un tempo multe corta, tu sabe—e estas, car los es juncos de sonia, fonde a via cuasi como neva, an cuando los reposa en montones a sua pedes—ma Alisia persepi apena esta, car el ave tan multe otra cosas strana per considera.

What mattered it to her just then that the rushes had begun to fade, and to lose all their scent and beauty, from the very moment that she picked them? Even real scented rushes, you know, last only a very little while–and these, being dream-rushes, melted away almost like snow, as they lay in heaps at her feet–but Alice hardly noticed this, there were so many other curious things to think about.

Pos vade no multe plu a ante, la plata de un de la remos deveni fisada en la acua e refusa es estraeda denova (como Alisia esplica lo a pos), e la segue es ce la manico de lo colpa el su sua mento, e, an con un serie de xilias peti de “O! o! o!” de la povre Alisia, lo puxa el direta de sur la seja, e depone el entre la monton de juncos.

They hadn’t gone much farther before the blade of one of the oars got fast in the water and wouldn’t come out again (so Alice explained it afterwards), and the consequence was that the handle of it caught her under the chin, and, in spite of a series of little shrieks of “Oh, oh, oh!” from poor Alice, it swept her straight off the seat, and down among the heap of rushes.

An tal, el no es doleda, e pronto senta denova: la Ovea continua sua tricota tra tota la tempo, esata como si no cosa ia aveni. “Tu ia catura ala un bon crabe!” el comenta, en cuando Alisia reveni a sua loca, estrema lejerida en trova ce el es ancora en la barco.

However, she wasn’t hurt, and was soon up again: the Sheep went on with her knitting all the while, just as if nothing had happened. “That was a nice crab you caught!” she remarked, as Alice got back into her place, very much relieved to find herself still in the boat.

“Si? Me no ia vide lo,” Alisia dise, cauta regardante la acua oscur ultra la lado de la barco. “Me desira ce lo no ia desteni—me ta gusta tan vide un crabe peti e prende lo a casa con me!” Ma la Ovea fa no plu ca rie despetosa, e continua sua tricota.

“Was it? I didn’t see it,” said Alice, peeping cautiously over the side of the boat into the dark water. “I wish it hadn’t let go–I should so like to see a little crab to take home with me!” But the Sheep only laughed scornfully, and went on with her knitting.

“Esce on ave multe crabes asi?” Alisia dise.

“Are there many crabs here?” said Alice.

“Crabes, e cosas de tota spesies,” la Ovea dise: “eleje entre multe, ma deside ja. E bon, cua tu desira compra?”

“Crabs, and all sorts of things,” said the Sheep: “plenty of choice, only make up your mind. Now, what do you want to buy?”

“Compra!” Alisia repete en un tono cual es partal stonida e partal asustada—car la remos, e la barco, e la rio, ia desapare tota en un momento, e el sta denova en la peti boteca oscur.

“To buy!” Alice echoed in a tone that was half astonished and half frightened–for the oars, and the boat, and the river, had vanished all in a moment, and she was back again in the little dark shop.

“Me ta desira compra un ovo, per favore,” el dise timida. “Como tu vende los?”

“I should like to buy an egg, please,” she said timidly. “How do you sell them?”

“Per un, sinco peniges e un cuatrim—per du, du peniges,” la Ovea responde.

“Fivepence farthing for one–Twopence for two,” the Sheep replied.

“Donce du es plu barata ca un?” Alisia dise en un tono surprendeda, estraente sua portamone.

“Then two are cheaper than one?” Alice said in a surprised tone, taking out her purse.

“Ma tu va debe come ambos, pos compra tu,” la Ovea dise.

“Only you must eat them both, if you buy two,” said the Sheep.

“Alora me va prende un, per favore,” Alisia dise, ponente la mone sur la table—car el pensa a se, “Cisa los va es vera mal, tu sabe.”

“Then I’ll have one, please,” said Alice, as she put the money down on the counter. For she thought to herself, “They mightn’t be at all nice, you know.”

La Ovea prende la mone, e pone lo a via en un caxa: alora el dise “Me pone nunca la cosas en la manos de la persones—acel ta conveni nunca—tu mesma debe prende lo.” E pos dise esta, el parti a la otra fini de la boteca, e sta la ovo sur un scafal.

The Sheep took the money, and put it away in a box: then she said “I never put things into people’s hands–that would never do–you must get it for yourself.” And so saying, she went off to the other end of the shop, and set the egg upright on a shelf.

“Me vole sabe perce lo no ta conveni,” Alisia pensa, palpante sua via entre la tables e sejas, car la boteca es multe oscur en sua parte final. “La ovo pare plu distante an cuando me pasea sempre plu en dirije a lo. E vide, esce esta es un seja? Ma lo ave ramos, me declara ja! Lo es tan strana ce me trova arbores cual crese asi! E vera, on ave asi un rieta peti! O! me ia vide nunca un boteca plu bizara ca esta!”

“I wonder why it wouldn’t do?” thought Alice, as she groped her way among the tables and chairs, for the shop was very dark towards the end. “The egg seems to get further away the more I walk towards it. Let me see, is this a chair? Why, it’s got branches, I declare! How very odd to find trees growing here! And actually here’s a little brook! Well, this is the very queerest shop I ever saw!”

* * * * * * *

* * * * * *

* * * * * * *

Donce el continua, sempre plu merveliante a cada paso, car tota cosas deveni arbores esata cuando el ateni los, e el previde intera ce la ovo va fa la mesma.

So she went on, wondering more and more at every step, as everything turned into a tree the moment she came up to it, and she quite expected the egg to do the same.

Esta paje es presentada con la lisensa CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

Lo ia es automata jenerada de la paje corespondente en la Vici de Elefen a 9 desembre 2025 (09:51 UTC).